DATELINE HOLLYWOOD

Germany Opens 62-Mile Bicycle Highway That’s Completely Car-Free

March 3, 2020

How Billie Eilish Is Reinventing Pop Stardom

March 3, 2020

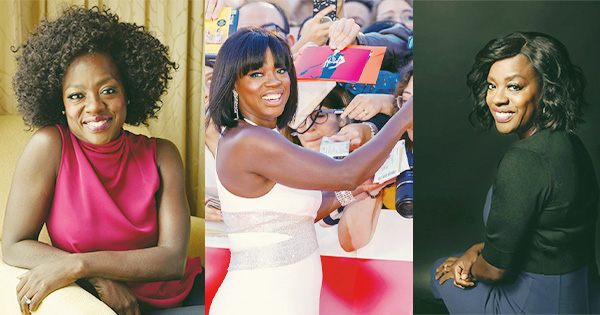

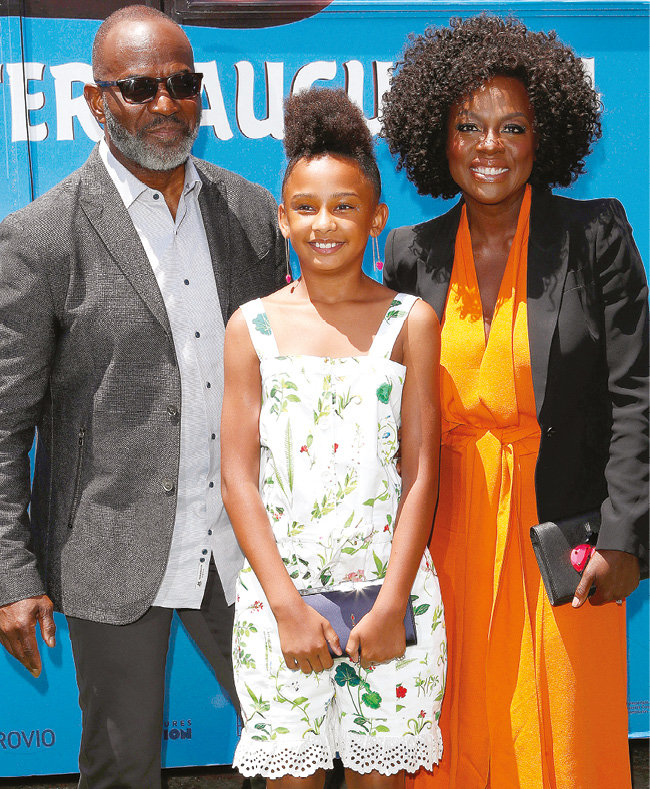

Viola Davis discusses her ongoing pursuit of that creative perfection

Richard Aldhous finds the actress current, connected and relevant

Viola Davis has a theory about her current Hollywood success and why she finds herself playing a string of roles that exude stoic strength in The Help, Doubt, Prisoners, How to Get Away with Murder, Fences and Widows.

“Whether it’s to do with my persona or my gravitas, I genuinely believe these roles are drawn to me because people feel I can inhabit them. They are of great size and I think people see me as someone of great size,” she explains.

Her deep tones ricochet across the walls while she slowly and purposefully rounds her vowels. It’s as if you’re sitting in the same room as Olivier and Leigh of old Hollywood. And then Davis comes out with words like ‘poop’ and ‘snot’ to bring you back to reality.

Success has definitely become a byword for Viola Davis. After plotting a significant path through a variety of small roles since her debut in The Substance of Fire in 1996, the actress moved to a place that she had previously thought unattainable with her Golden Globe and Oscar winning performance in Fences.

Davis is a fascinating encounter of grit and determination, leading to triumph and success. Thankfully, the Hollywood machine has done little to tarnish her unique persona. Fran----kly, the exposure to the red carpet has only served to reinforce her grounded rugged and sometimes scathing opinions of the celebrity circuit. In addition, it has opened up the actress to the clear dramatic space created by TV drama, which is an area that has breathed new life into the industry.

Across How to Get Away with Murder, American Koko, and before that United States of Tara, Law & Order: Special Victims Unit and Traveler, Davis has proved her ability to mix short form drama with more considered and impassioned displays of raw dramatic power and emotion.

“I think the demand these days is very much for versatility. The formats are different, the characters are different, the storylines are different… and yet, the audience is the same. And they want to be entertained,” Davis observes.

This year, as far as Viola is concerned, that entertainment arrives predominantly in the form of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom. Set in Chicago in 1927, it tells the story of the so-called ‘Queen of the Blues’ who – while making a record – falls out with her producer, agent and bandmates.

Typically, it’s another culturally appropriate project for the actress, and one that confronts race, social status, creativity and repression. Taking the form of a Netflix movie adaptation (based on the 1982 play by August Wilson), it treads familiar ground for Davis in terms of subject matter whilst furthering her trail of discovery away from traditional cinema and onto the small screen. It’s a diversion that she is comfortable with.

“It’s almost become the norm now that any film project stands a chance of being grabbed and taken away onto television"

Davis opines: “It’s almost become the norm now that any film project stands a chance of being grabbed and taken away onto television. I don’t see that as a bad thing. Ultimately, the way we view this shouldn’t be a problem whether it’s at the picture house or at home.”

The actress surmises that the biggest challenge is the format rather than the content itself. She implores producers, directors, and those in cutting rooms to take responsibility for the way they retain and respect the work of actors.

She elaborates: “You know, what we ultimately have in the world of cinema is a wanting to make everything pleasant and obtainable. I could speak of countless producers, directors, and actors I’ve been around, in the very heart of the most emotional and stirring scenes in movies, which really have the potential to drive controversial and true stories of what happened in history.”

“And guess what happens… those scenes are cut. I have said this before but it’s the most punishing part of the process for a number of reasons,” Davis says.

Viola continues: “I think we need to be strong and pioneering about the extent and lengths we go to when we’re trying to create original cinema. The future won’t thank us for dumbing down the realities of life – like we don’t thank the past for the soft silly versions of very real tragedies that were played out to us.”

Clearly, Davis has a point; but in the sanitised world of cinema, entertainment and news, the threats to risk takers are the very things keeping creative minds back. “That may be the case now,” she says, pointing at her phone and adding; “But I genuinely believe that we may be on the way to change.”

Viola adds: “I think the wideness of social media will force filmmakers to step up their craft and really deliver the true stories that people want. If we are not to get them in film, then we’ll simply turn on our phones and computers, and consume the content knowing we’re watching real life instead.”